|

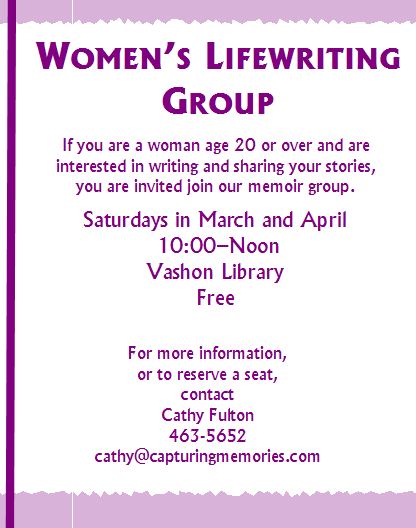

| Facilitating a Lifewriting Group is Easy,e-book (instant download) is currently on sale for 9.95! |

- You probably don’t want to place anything precious or costly in them.

- You can’t include items that belong to another family member or that you are currently using.

- Over the years, you have probably misplaced or given away some excellent candidates for the capsule.

- Some items are just too big!

Make a list of 10–12 items from your life that evoke memories. You don’t have to currently possess each item. Take some time to think about this. Choose items from different time periods—childhood, teenage years, early adulthood, etc. Try to span your entire life. For some, this is not as easy as it sounds. When I started my list, I had a hard time coming up with objects. By the time I got to the end of my list, I couldn’t stop thinking of them! Some suggestions for items to include are: toys, mementos, certificates and diplomas, works of art, tools, kitchen gadgets, articles of clothing, crafts, journals, and pets.

It is important to limit the number of items before you begin listing them. This ensures that you think carefully about the value or importance of each thing you include. If you find yourself listing too many items, it is okay to go back and replace a previously listed item. Don’t bother to list them in any special order—just get them down.

Here are some examples from my list: and old pipe I bought in Israel, an aquamarine ring, dirndl (dress) from Salzburg, Girl Scout sash, lock of hair, pink sand from Utah.

Now for the fun part! For each item, answer the following questions:

- When did you own it? (Include your age.)

- How did you come to possess it? Who gave it to you? Why did you acquire it?

- Where did you live when you owned it?

- What was it used for?

- Did someone else possess it with you? Who and why?

- Do you still have it? Is it something you hope to pass on to another family member?

- Why did you select it to include in this “time capsule on paper?” Why was/is it special to you?

- If you no longer have it, do you have a photograph or sketch of it?

Now start your paper time capsule. When you are finished, seal it away with instructions about when and by whom it is to be opened. The great thing about this kind of time capsule is that you can make several copies—one for each grandchild, for example!

Additional Time Capsule Ideas

- Make a list of fifty-two items and write about one each week for the next year.

- Ask another family member or friend to write or otherwise record their remembrances of some of the items on your list.

- Go further—put together a family paper time capsule. Ask each family member to “contribute” three or four items. If they do not want to write about them, get them to record their memories on audio tape, which you can later transcribe.

- Bind your memories: a time capsule in a book!

Facilitating a Lifewriting Group is Easy is available for purchase in both a hardcopy (printed) form and as an instant download (e-Book) at my Capturing Memories Store. Visit the store to freely download the Introduction, Table of Contents and Chapter One.